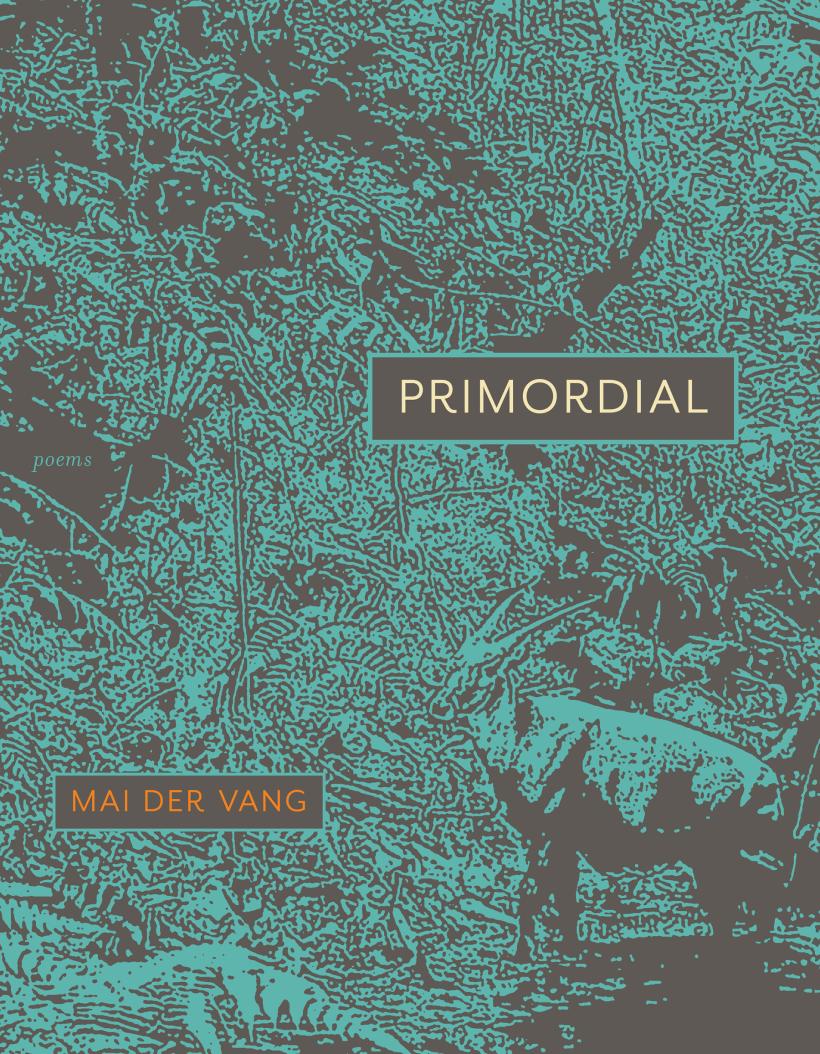

Written by Pulitzer Prize Finalist Mai Der Vang, Primordial is a hybrid poetry collection that was released on March 4th by Graywolf Press. Sitting at 155 pages, Primordial is on the beefier side as far as poetry collections go, and for good reason. Primordial covers many subjects, all of which connect to our collective need to fight against extinction and exist with dignity and environmental unity on our planet. Therefore, it is only natural that this collection is split into eight sections, which oscillate between depictions of the critically endangered saola, colonization, the history of the Hmong people, Vang’s experiences with pregnancy loss and growing up in a Hmong family in California.

To begin: what is a saola? A saola is a bovid native to the forests in the Annamite Range in Vietnam and Laos. It was originally discovered in 1992, and according to Vang’s ekphrastic poem “Camera Trap Triptych,” the first photo of a wild saola was taken in Pu Mat National Park, Vietnam, in 1998. And considering the fact that it is critically endangered, it only makes sense that its last known sighting was in 2013, 12 years ago. Its population has dwindled to this extent not only because of its limited (and fragmenting) habitat, but also because of local hunters. All of this to say: the saola is the perfect motif through which Vang can discuss the Hmong people and her own life.

Like the saola, the Hmong people have been hurt almost beyond repair. In the 1960s, the CIA in the U.S. recruited Hmong people to fight a “secret war” against the communist government of North Vietnam and the communist political movement called the Pathet Lao. Also like the saola, many of the Hmong people were displaced from their homes, causing them to move to other countries, including the U.S. In Primordial, Vang closely relates the saola with the Hmong people, as if the two are symbols for one another. This is not only because of their shared geographic location, but also because of their shared historical urge to hide and seek refuge. A great example of this comparison in Primordial is in Vang’s poem titled “Evolution, Absence,” where her Hmong personhood, the Hmong people as a whole, and the saola are depicted as preferring privacy, needing to “secret” themselves in order to survive. At the same time, Vang claims that all three do not need to be seen in order to exist with dignity.

I describe this collection as hybrid for a couple reasons. First of all, Vang experiments with a variant of “Node” poems, which, in the case of Primordial, are timeline-like word structures. Under a punctuated line of dots, bolded sentence fragments come together to form a sentence. In between (and growing out of) these lines are strings of non-bolded text that branch out like an evolutionary line. From a purely representational perspective, these Node poems serve as the glue for the collection, abstractly undulating between the aforementioned themes. However, I did find them difficult to read at times, largely because of how nonlinearly you have to read the lines. On some branches, you have to read clumps of text ascending upward, and that can get confusing on top of the already layered subtext and syntax. It didn’t take too much away from my reading experience though, as the Node form serves an important visual purpose considering the themes exhibited in Primordial. In addition, some of the later Node poems dip into themes of Vang’s pregnancy loss, which are not only confessional but connect back to this collection-wide theme of the fragility and interconnectedness of life.

Another reason this collection is hybrid is because of some of its longer poems. Poems like “I Understand This Light to Be My Home” are powerful because of their length. In that poem, Vang uses dense clusters of the words “Language” and “Light” to suggest that every life form comes from light, and that the language we use comes from light as well. To use our bodies as tools of violence against other creatures, by this logic, is a kind of suicide. Watching the cluster of “Light” become more dense as the pages turned tugged at my heartstrings.

Overall, one aspect I wanted to see explored a bit more in Primordial was concrete actions we as consumers and readers can take to protect our environment and the saola. Perhaps the suggestion Primordial is making is that we let the saola run free. If we let the saola run free and repopulate and return to its habitat, we will be protecting a beautiful, prehistoric part of our biological lineage. Maybe life is less fragile when we let it run free and stop trying to kill it at its source.

(Thank you to Graywolf Press for the ARC of Primordial by Mai Der Vang! It was an honor to review it.)