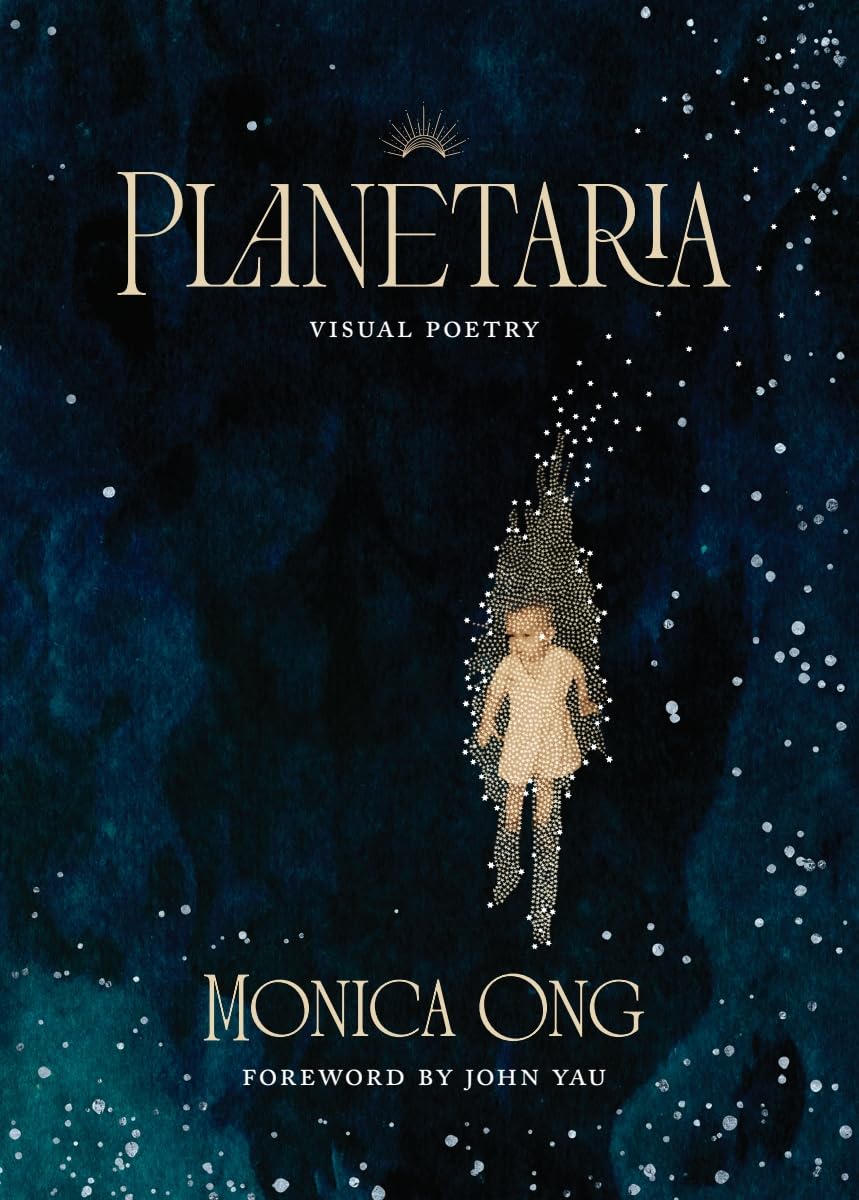

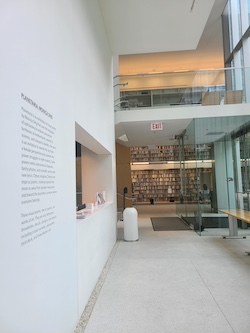

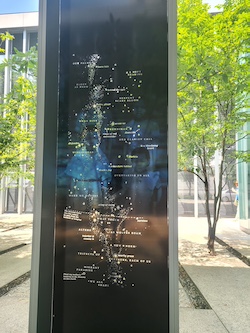

I first had the pleasure of coming across Monica Ong’s poetry when seeing her work from Planetaria: Visual Poetry (Proxima Press) on display at the Poetry Foundation in 2022. This, I believe, is the most natural way to discover a visual artist / poet: a gallery of sorts is required to digest the full breadth and luminosity of the work. Upon first experience, what I took away from Ong’s work was her use of the universe and stars as a way to zoom out and see ourselves and our micro family units and stories from a cosmic lens. It had the scope of the “butterfly effect”; our little lives make waves across the universe and beyond, and while the minutiae will be forgotten, writing is a rebellion against the fleeting nature of memory and our individual lives.

“Poets are selenologists learning to read craters of loss.” – Monica Ong, from “Jade Insomnia” (p 44)

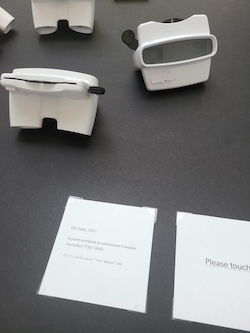

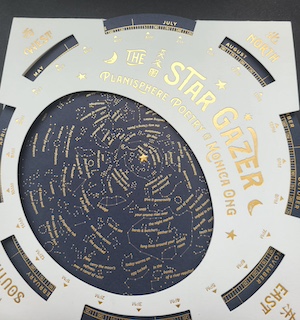

Ong’s juxtaposition of mostly 19th-early 20th century diagrams of outer space with old photos of the author’s family as well as with the poetry and text often visually becoming a part of the stars and planets (but sometimes apart from it), is crucial in firmly establishing their relevancy to one another and taking the macro lens of viewing our place in the universal. Out of maps of the solar system and from the “anxious study of patterns and vertices that squint for a brand new design” (p 29), Ong creates new language and new images. What I also found interesting in the book was that images of 3D objects (some I could still remember feeling from my exhibiting of the art pieces a few years ago — several pieces were meant to be touched — Ong’s “orchard of handheld poems”), were often followed by text-only forms, therefore almost three translations were taking place: a 3D object translated to a 2D photo translated to a text-only poem on the page. Furthermore, the visual poems broke from the limitation of the English rule of reading from left to right, opening up the possibilities of how to read or enter it, and where to go along the way. I found this experience fascinating and it added metaphorical textures, with the viewer as an active participant in recognizing the paradoxical ephemerality and “improbability” of our existence, the gravity of loss, and the timeless, partial immortality of the art itself which explores these seemingly small, yet looming, brief and very human experiences.

She invites us into the experience with: “Come. Nestle in the kinship of our gorgeous insignificance” (“Feather,” p 27). Her themes come into focus even more clearly with the strikingly modern imagery in text beside the old photographs and older diagrams. Moving seamlessly from visual imagery, visual poetry, delineated poetry, to prose poetry, she expertly crafts, “Ink blots billow into a milk-strewn sky, curving to the traffic of car streak stars” (p 37). When it comes to pain, furthermore, she asks us to “take comfort in knowing that this year is but a blink in the breath of trees and cosmic moss” (p 37). She reassures us when she implies that if we zoom out, as her work implores us to do, we can more clearly distinguish “the wound from the body, the body from the wound” (“Yellow Insomnia,” p 59), and see our part in the bigger picture with a more “whole” vision of ourselves, others, and the world.

“Between / the STARS / are stories / of loss.” – Monica Ong, from “Red Phoenix” (pp 23-24)

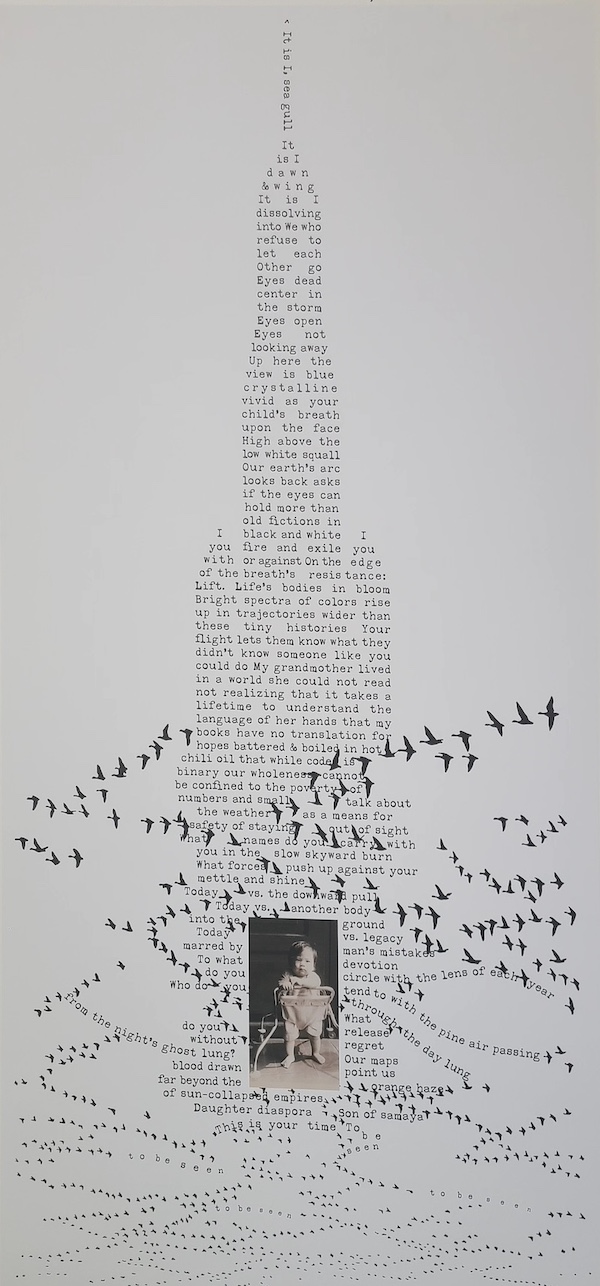

Motherhood and womanhood are also key themes in the book, with the symbol of milk appearing as both mother’s milk and in the Milky Way (or “The Way of Milk”). To drive this iconography further, the universe itself is compared to a nipple in “Woman’s Place in the Universe,” a prose poem about a woman astronomer (in direct contrast with it’s chosen diagram, which was taken from Man’s Place in the Universe): “She turned her garden into a laboratory to decipher the secret turning of the stars…she glimpsed her face in the lunar mirror’s gleam” (p 32). As an ode to all women (and mother) discoverers, she writes, “There are those whose greatness grows in shadow, whose outer limits the spotting of blood cannot contain” (p 32). For the narrator, these societally-imposed limitations and binaries are preposterous: “while code is binary / our wholeness cannot be” (“Seagull,” p 68). This is further highlighted within “Book of Vera” (p 40), a poem about Vera Rubin, who we learn was an astronomer who, when granted access to San Diego’s Palomar Observatory in the mid-1960s, was told that there was no women’s restroom. The narrator (“I”) equates herself with Vera Rubin (“you”) in a brilliant ending to the piece:

Beneath this concentrated scowl, I am a girl searching…

for the observatory bathroom, echoing the hallway where you firmly pressed

onto the door a cutout paper skirt and said:

There you go; now you have a ladies’ room.

“Insomnia” is threaded throughout the book, the narrative being of a mother who is awake at night, perhaps feeding her children and/or creating works of art, or both (perhaps there is little difference in the grander scheme of things). In “Amber Insomnia,” “what one does and what one wants to do” are “separated by the sap of a golden hour.” The narrator is not afraid to work, to care for their family; her children are also metaphorically stars, including shooting stars with their own stubborn and unpredictable trajectories. Additionally, the stars watch or rule over us as “manmade gods.”

I found myself smiling as I “starred” my favorite moments in Planetaria. I laughed as I said to myself, “All her poems are stars.” The symbol of the star and its power is deeply ingrained in our society, from getting a star at school for good work to starring important lines in a book of poetry. While we are all always connected to this bigger picture, Ong sets the connection in full view, reminding us that we are small specs of earth who must work for our dreams to come to fruition, even if we cannot determine their trajectory, even if our end is ultimately to rejoin in our place among the stars, with the nuances of our existence being remembered and told through family stories, if we are lucky.

Another prominent theme in Planetaria is migration; Ong’s parents were refugees who emigrated from China to the Philippines, and then to Chicago, Illinois. Multilingualism is central to the work, as well. These aspects of identity, family history, and ancestry are importantly incorporated throughout. In “Solstice Blessing,” the experience of migration is equated to moths fluttering to a flame, highlighting the danger “to flutter in the / places that / burn” (pp 9-10), and the weight of loss and familial expectations loom in “Jade Insomnia,” where the “sky is heavy with other people’s dreams” (p 44). Looking for home, we find that it is not city, not country, not even just earth — but the whole universe is our home, even if we are “watched by eyes that never learned to see us whole” (p 59) — and we’ll continue to prove them wrong again and again. Ong quotes Wang Zhenyi (1768-1797), “Are you not convinced, / Daughters can also be heroic?” (p 32) The most important things in this world, she implores, are our stories, which will be made of the answers to these four vital questions: “What names do you carry with you / in the slow skyward burn”?; “To what devotion do you circle”?; “Who do you tend to”?; and “What do you release without regret / from the night’s ghost lung?” (p 68).

After a thorough examination of the blood-drawn maps of a history “that was never written for me” (“The Daughter’s Almanac,” p 60), Ong precedes to write her own, and invites others to do the same:

“On this day / I choose…to / pencil in the marvels / I’m here to set in motion… / the trajectory of our shared arc / and the blade of my gaze // my gaze” (“The Daughter’s Almanac, p 61).

Although I encourage you to catch a 3D exhibit of Ong’s work if at all possible, a copy of her book of visual poetry is nonetheless essential for long-term viewing, like a travel coffee table book, but these pages will open up windows to the universe and the soul, not just to the limited and superficial world as we have come to know it today through pictures shared via the click of a button on social media. In her interview for the Tenet podcast, Ong describes how her visual art education and studio training background influenced how she works with text: whenever she writes poetry, she thinks, “How would this poem exist both on the page and off the page?” Existing in both is exactly what she accomplishes with Planetaria.

Poetry as visual element is like a door or window — it tells you something about itself before you enter within its framing. It draws you in with its daring, unique structure. It is a radicalism (visual poetry) upon a radical form (poetry) of a radical medium (art). It tells us something about ourselves that is long-lasting and poignant. We crave to be seen. We crave to be understood as much as we crave to see and understand. Art, poetry, and visual poetry provide a window, or a door, that the reader must dare to enter.

“Daughter diaspora

Son of samaya

This is your time

to be seen

to be seen

to be seen

to be seen”

(From “Seagull,” p 68)